You’ll know the story already, I guess. Heroic. The tramp steamer Stanbrook.

And its legendary Cardiff skipper, Archie Dickson.

The tragic closing days of the Spanish Civil War. 28th March 1939 and a final desperate group of Republican refugees carried to Oran, North Africa. To comparative safety. Out of rebel General Franco’s clutches, the almost certain death they would have faced if they’d fallen into his hands.

Among them, loyalist soldiers like Amado Granell Mesado, who’d already been fighting Europe’s Nazis since 1936. Granell and others would continue that struggle by eventually enlisting in the forces of Free France and, as part of a Spanish company, La Nueve, be the first Allied unit to fight its way into Paris as part of the city’s liberation, in August 1944.

A remarkable story.

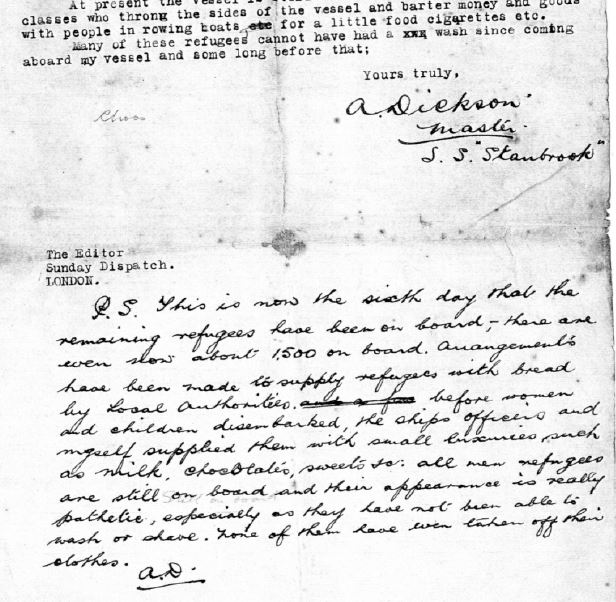

But it’s not without its mysteries and points of contention. The numbers of passengers carried to Oran on board the Stanbrook, for example. The generally quoted figure is 2,638, though Dickson himself put the figure somewhat lower. In a letter he wrote from Oran to the Sunday Dispatch literally just a couple of days after their arrival, he says: Eventually at about 10.30pm the last of the refugees were aboard…and I subsequently ascertained later on that there were 1,835 in all.

Meanwhile, Alicante-based political journalist David A. Rubio de Antón, who’s studied the actual passenger lists recorded by the French authorities in Oran, puts the figure as high as 2,850: https://alicantepedia.com/bases-de-daros/stanbrook-pasajeros-y-tripulaci%C3%B3n But there seem to be plenty of duplications on the list and it’s at least possible that passengers include some of those who’d actually arrived in Oran on board other vessels from Alicante, like the African Trader and the Ronwyn.

The highest estimate I’ve seen puts the figure at well over 3,000.

Does the precise number matter? Not for me. By any reckoning, this was a remarkable feat.

Ted Richards, chairperson for the Roath Local History Society has a wonderful blog piece tracking Archibald Dickson’s early days and career: https://roathlocalhistorysociety.org/2021/08/20/archibald-dickson-an-unsung-roath-hero/

In summary, Archie born in Cardiff, 1892, one of thirteen children. By 1939 he was living in the city’s Roath district with his wife and kids.

From that letter to the Sunday Dispatch and lots of other sources, we know that the Stanbrook (and Dickson) had already made two previous voyages to Republican Spain, that she was a small general cargo vessel – not, at that time, a collier as some accounts insist, though this was the purpose for which she’d originally been built, back in 1909. 1,383 tons, 230 feet long, 34 feet in the beam, with an approximate speed of 11 knots, and accommodation only for its crew of 24.

The skipper explains that on 17th March 1939 he received orders from the Stanbrook’s owner to proceed in ballast to Alicante from Marseille. The voyage was unremarkable except for having to avoid a Francoist destroyer in a squall, and they arrived in Alicante around 6.00pm on 19th March. But in Alicante there were no instructions, Dickson tells us, about the cargo he was to take “or anything else.”

Now, what does that mean? Or anything else? It’s generally assumed that Dickson was a regular skipper, in Alicante to pick up a regular cargo, and then simply persuaded by his own conscience, instead, to fill his vessel with refugees.

But might there be a deeper story?

After the Stanbrook docked in Oran, she was impounded by the French authorities – in part, at least, a retaliation for having all these refugees brought to their French colonial shores. The refugees themselves – as in mainland southern France – were treated very badly indeed, forced to stay on board in the most inhumane conditions and, when finally allowed to disembark, thrown into equally inhumane internment camps.

The Spanish politician and trade unionist Rodolfo Llopis (Alicante’s Diputado in the Spanish Parliament, as well as General Secretary of both PSOE and UGT) was responsible for the negotiations between the French authorities and Juan Negrín’s Republican Government in exile. The French initially demanded 205,000 French francs for the Stanbrook’s release, then raised the amount to 250,000 and finally settled on 170,000.

Recently, from the Bruno Vargas biography, based on the politician’s personal archives, it seems Llopis had been responsible for earlier negotiations between the Republic’s various agencies and shipping companies or owners to specifically organise ships for refugees. Those companies seem to have included the Stanhope Steamship Company, owned by Jack Billmeir, and there’s a thread which implies that Billmeir may have chartered the Stanbrook to the company France Navégation, an organ of the French Communist Party, specifically to help transport Republican refugees and as a blockade runner.

It’s important to remember that, while skippers like Archie Dickson may have been heroic, there are few philanthropic shipowners. For many, possibly Billmeir among them, trading with a beleaguered and desperate Republican Spain could be a profitable business.

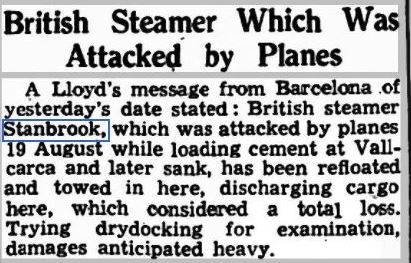

The Stanbrook had already been attacked, once in August 1938, when Italian planes had bombed her just south of Barcelona – so badly damaged that she had to be refloated and substantially repaired – and then bombed again in February 1939.

That previous voyage, from Alicante to Marseille, had certainly been for the purpose of carrying refugees. Some of this is also covered in the articles written by Alicante University’s Professor of Geography and History, Juan Martínez Leal: file:///Users/davemccall/Downloads/Dialnet-ElStanbrook-2161758%20(2).pdf.

It’s only a piece of personal speculation, but I think there’s enough room here to believe that Archibald Dickson may have been back in Alicante with a double brief – to collect a commercial cargo and to collect another cargo of refugees. There certainly seems to have been some confusion. Let’s go back to Dickson’s letter. This is what he says:

On the 26th March I proceeded to Madrid and ascertained from officials there that the cargo for my vessel was in lorries on the way.

Proceeded to Madrid – why? And ascertained from “officials”? In those final chaotic few days before the curtain finally fell? Officials still interested in such a modest commercial cargo? Dickson’s subsequent comments almost express surprise when the oranges, tobacco and saffron turn up. Then a thousand refugees arrive in trucks at the Custom House and the authorities ask him to take them on board. Were these in fact “the cargo” that had been on its way in lorries?

But then there were all the other refugees on the quayside. All classes. Women and children. Dickson says this put him in a quandary, since he had instructions not to take refugees unless they were in real need.

However, as we know, he didn’t procrastinate very long. The oranges, saffron and tobacco were left on the quayside, and he loaded far more than the initial thousand on board his ship.

Those he couldn’t carry? Many committed suicide, rather than fall into Franco’s hands when Alicante fell, after further bombing, just a few days later. Thousands were marched off to the quickly established concentration camps in the town’s bullring, or at the Campo de Albatera and the Campo Los Almendros. Many were summarily executed by Franco’s death squads.

Reading the Archibald Dickson letter afresh, and taking the Rodolfo Llopis archives into account, I’m now more convinced than ever that his intended “cargo” were the 1,000 refugees he was officially asked to carry, plus the oranges, saffron and tobacco – and that he then exceeded his orders by replacing the oranges, saffron and tobacco with those additional 800-1800 passengers.

One way or the other, by the time the Stanbrook reached Oran, Rodolfo Llopis was already there from Paris, expecting her arrival. It was Llopis, among others, who helped mobilise the Spanish community in Oran (there were significant longstanding Spanish communities in most of the coastal towns and cities of Algeria and French Morocco) to carry food and drink out to those trapped aboard the Stanbrook and, of course, to eventually secure her release.

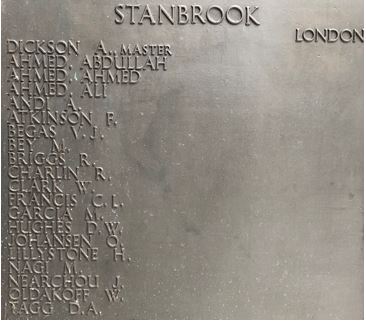

The ship’s story ended tragically. Later that same year, with the Second World War now begun, the Stanbrook was attacked by a German U-boat in the North Sea on 19th November 1939 and sunk with the loss of Archibald Dickson and his entire crew. They’re all mentioned, by name, on London’s Merchant Navy War Memorial. The same mixed crew, more or less, which took part in that remarkable voyage from Alicante, eight months earlier. A mixed crew: the Yemeni, Ahmed bin Ahmed; the Swede, Oskar Johansen; the Spaniard Ramón Charlin; the English First Engineer, Henry Lillystone; and several Welshmen, including Archie Dickson himself. The others who died with them.

But slowly their story is being remembered. There’s now a memorial, a plaque and a bust of Archibald Dickson, on the quayside at Alicante.

And a street in town name Calle Buque Stanbrook.

In Cardiff, a plaque presented by the Comisión Cívica de Alicante Para la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica can now be seen inside the city’s waterfront Pierhead Building, unveiled there on Tuesday 10th May 2022 by the First Minister of Wales, Mark Drakeford, in conjunction with the Cymru section of the International Brigades Memorial Trust. Unveiled largely thanks to the work of IB Cymru activists (and friends) like Mary Greening, or Malcolm and Lorraine Hardy from the IBMT, as well as many Spanish comrades within the Comisión Cívica de Alicante and elsewhere.

A remarkable story indeed!

The story of the Stanbrook features in the closing chapters of Until the Curtain Falls, while the tale of some of her passengers, Amado Granell among them, is picked up in A Betrayal of Heroes. For a more detailed study of the background, see the book by Graham Davies: Outwitting Franco – The Welsh Maritime Heroes of the Spanish Civil War.

Dave, fascinating story.

Do you mean the 22nd of May 2021 perhaps?

Hi Rory. Glad you liked it. And apologies for being dim – but 22nd May 2021??? Do you mean the date of the unveiling by Mark Drakeford in Cardiff? This was last week, 10th May 2022, though I might have confused things by writing the article beforehand (end of April), so that I could get it in the newsletter, and knowing that the Cardiff event was coming up. So, wrote the piece as though the event had already happened. And then I wouldn’t have to edit again afterwards. Lazy, or what? But I did list the event in the diary dates bit, as well. Or am I barking up the wrong tree here? Apart from all that, hope you’re keeping fit and well.

Hi David

My Great Grandad was on the Stanbrook when it sank in Nov 1939

I’m trying to find out when he Joined the ship

Do you know the crew list in March 1939 ?

Thanks

Ian Clark

Hi Ian. Apologies for the delay in getting back to you. I don’t have the crew list for March but I read somewhere (can’t remember where) that the crew was almost entirely unchanged during most of 1939. If your great-grandad was aboard when she went down it’s almost certain he’d have been at Alicante. Email me his name maybe? (davemccall@davidebsworth.org) And thanks for being in touch.

Hi

My grandma & her family left from Alicante in late March 1939, they don’t appear on the Stanbrook list, my grandma always said it was the last ship, but she also said it was French…& they took their stuff for the crossing? I have letters my great grandfather wrote from the camp in Algeria.

Any ideas ref passenger list? The Ronwyn perhaps?

Hi Leila. Apologies, since I only just saw the comment. When I was researching the Stanbrook story, I came across this snippet… “there’s a thread which implies that Billmeir may have chartered the Stanbrook to the company France Navégation, an organ of the French Communist Party, specifically to help transport Republican refugees and as a blockade runner.” And that might explain the “French” connection. But I don’t think that would apply with the Ronwyn. On the other hand, I vaguely remember mention of a French vessel as well – though it was some time ago and I can’t remember the details. I’ll try to remember! Better still, I’ll mention this to researcher Eliane Ortega, from Oran (you can find her on Facebook), who knows more about the Algerian exodus than the rest of us put together. If you want to give me grandma’s details I’ll send them off to Eliane and see if she can track down more information for you. Email me, maybe, at: davemccall@davidebsworth.org. But thanks for making the contact!